As you can imagine, there are many different kinds of questions to ask in surveys. And the variety doesn’t just extend to topics—it also refers to the way questions are framed, posed, and answered.

The Likert scale is one such type of question. So, what is it? And how is it used?

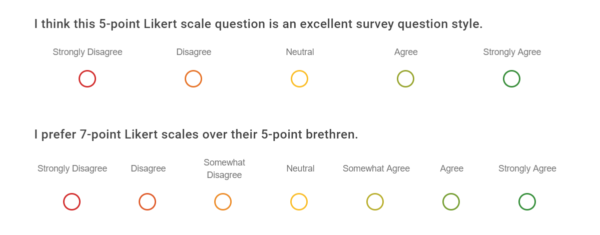

In short, the Likert scale was a 5- or 7-point scale developed to quantify feelings. But to better understand it—and how to use it—we’ll have to start from the beginning.

Introducing the Rensis Likert

Let’s start with some basics. “Likert” is not pronounced how it looks. It’s not “lai-kert,” it’s “lick-ert.” It’s pronounced this way because it’s actually someone’s last name, and there’s no predicting how people pronounce their names. Most people say it wrong though, so in case you do slip up, at least you’re in good company.

In 1932, the Psychologist Rensis Likert decided that he needed a way to quantify the strength of people’s emotions. To keep things simple, he developed a linear scale for psychometrics—the measurement of feelings.

The idea was that a scale could ask people how they feel about something. His scale requires people to answer by identifying how they feel about—or to what extent they agree with—any given statement.

He began asking, “On a scale from 1–5, how strongly do you agree with this statement…”

What Likert Scales Look Like

You’ve almost certainly seen (and probably used) Likert scales before. They’re exceedingly common. Part of that is because they work so well, and part of that is because they’re recognizable and easy to understand.

Likert items—that is, statements to be evaluated on a Likert scale—are presented with several optional responses. Usually, they go

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Undecided/Neutral

- Agree

- Strongly agree

But still, what do they look like? They look a little something like this:

Generally, Likert scales are odd-numbered. Most often, the scales span only five or seven responses. The odd number is important:

Because Likert scales measure intensity of feeling, neutral options keep results in line. Even-numbered scales don’t allow people with little or no opinion to express their lack of emotion or intensity. Here’s why:

For example, we know water is flavorless. If a survey prompts, “I love the taste of water,” most people would have a neutral response.” On a 7-point Likert scale, “4” would be the obvious choice. It’s hard to like the flavor of something that doesn’t taste like anything!

Nevertheless, even-numbered Likert scales do exist, and they do have their place. Sometimes, neutral responses can be cop-outs. Even-numbered Likert scales force respondents to take a position.

How to Use Likert Scales

Likert scales are best used to gauge how people feel about specific goods, services, or experiences. They can be used for many purposes:

- To gauge interest in an upcoming or potential product

- To measure experiences, either on-premise or from a call center

- To learn consumer preferences, such as preferred contact methods or times

There are many other uses, too. In many ways, the use cases for Likert scales are limited only to a survey-taker’s imagination. But, to better illustrate how several Likert scale questions could find different angles about the same subject, let’s explore what happens when a credit union wants to offer a rewards card, but they want to gauge interest. Here are three questions they might want to ask that could be answered with a 5- or 7-point Likert scale:

- “I use or prefer to use credit cards for everyday purchases.” This question ascertains whether the credit union members would use their credit cards for local or recurring purchases.

- “I prefer to use credit cards that offer rewards over cards with lower rates.” This question learns whether people would like a rewards program—or if they’d be better off by promoting low rates or balance transfers.

- “I would use a card from my credit union over another provider such as Capital One or American Express.” This question determines whether the credit union’s card would be competitive with other offers. (Share of wallet is a major income driver for financial institutions.)

When we put together credit union member surveys, we usually throw in a few Likert scales. They allow us to measure how our members feel about our various services.

To continue the theme, other credit union examples might prompt, “The mobile banking app is easy to access,” or, “I find the online banking website easy to navigate,” or, “I use my credit card for all major purchases.” With the resulting data, we can see trends in member sentiments that we can use for broader strategic purposes, measuring member experience, and so on.

If you’re throwing together a survey about your credit union’s services, including online and mobile banking, wait times, ATM or branch access, or staff helpfulness, consider using a Likert scale.

Further Reading

If you’d like to read more about credit union surveys or survey strategy, subscribe to our blog! We keep it full of helpful survey tips and tricks, plus we include ideas about what to do with your survey responses when they start trickling in.

Or you can just follow the links below to see what else we’ve written lately. If you’ve made it this far, then we’re sure you’ll like it.